Back when I started working in digital marketing, and much of the work centered around new lead capture, I’d often remark that people’s most valued currency online is their personal information. The statement may have been a bit self-serving as our edict was often to capture that information for our clients, but in practice, it generally proved to be true from 2000 to about 2015. Now, I’m not so sure that’s true. Sure, people claim to be concerned about protecting their personal information – and flare ups like Facebook’s recent Cambridge Analytica scandal or the Equifax data breach, will continue to dominate headlines. But in practice we are trending towards more disclosure, not less. These scandals will be more cautionary tales than moments of punctuated equilibrium and change. And while in the old days, asking for a person’s contact information was often a bridge too far, now, despite most saying they are concerned about privacy online, people are ever more willing to share their most personal details on their devices, including personal health information, without fully considering the risk. A 2016 Pew Research study found that just 12% of Americans have a high degree of confidence in their security of their information and 49% felt their information was less secure than it was 5 years ago. Yet, despite this concern, most Americans aren’t taking basic actions to protect themselves: the same Pew study found that 69% of American adults online don’t worry about the security of their passwords and, even people who have reported being impacted by a data breach are no more likely than the general population to take steps to secure their passwords.

We’re optimistic about ourselves, we’re optimistic about our kids, we’re optimistic about our families, but we’re not so optimistic about the guy sitting next to us.”

Cognitive Neuroscientist, Tai Sharot

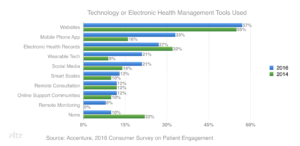

While people say they are concerned about data privacy, they aren’t proving it in how they act. One reason may be rooted in the optimism bias, a sense that discounts the possibility that they may experience a negative event, a phenomenon that cognitive neuroscientist Tai Sharot described in her TED talk as the sense that “We’re optimistic about ourselves, we’re optimistic about our kids, we’re optimistic about our families, but we’re not so optimistic about the guy sitting next to us.”  Another reason in healthcare may be the growth and increased usage of health technology, from Electronic Health records to collaborative care platforms and telehealth solutions. These platforms are increasingly bridging the cognitive gap between devices and doctors. When you can access a secure environment to see all of your health records through an EHR’s patient portal or when you speak directly to a physician through a telehealth application, we seem to be effectively expanding people’s notion of a safe space for personal health disclosures.

Another reason in healthcare may be the growth and increased usage of health technology, from Electronic Health records to collaborative care platforms and telehealth solutions. These platforms are increasingly bridging the cognitive gap between devices and doctors. When you can access a secure environment to see all of your health records through an EHR’s patient portal or when you speak directly to a physician through a telehealth application, we seem to be effectively expanding people’s notion of a safe space for personal health disclosures.

It’s just like talking with your doctor. If I tell the app more about me, it will be more useful.”

While we aren’t there yet, the trend seems to be towards people equating devices with doctors. As one 44-year old man suffering from a chronic disease told our team “It’s just like talking with your doctor. If I tell the app more about me, it will be more useful.” And while people of all ages’ behaviors are shifting towards more health disclosures online, younger people’s usage of social media for health related purposes (37% of people aged 18 to 33 compared to 8% of all adults according to a Deloitte study), suggest that this trend will only accelerate over time. So if people are more willing to share personal health information online, what’s the responsibility of digital marketers in the health and pharmaceutical space? We’d suggest that it starts with a new Hippocratic oath for digital marketers: First do no harm. We need to respect people’s trust above all else, keeping any disclosed information secure and guiding people to adopt safer behaviors online, even if they are less inclined to do so themselves. That said, data security is a topic unto itself, one that is better left to others with more expertise in that area. As user experience designers, our focus is on the value marketers can provide when people do disclose personal information, value we’d group under the headlines of empathy, simplicity and expertise.

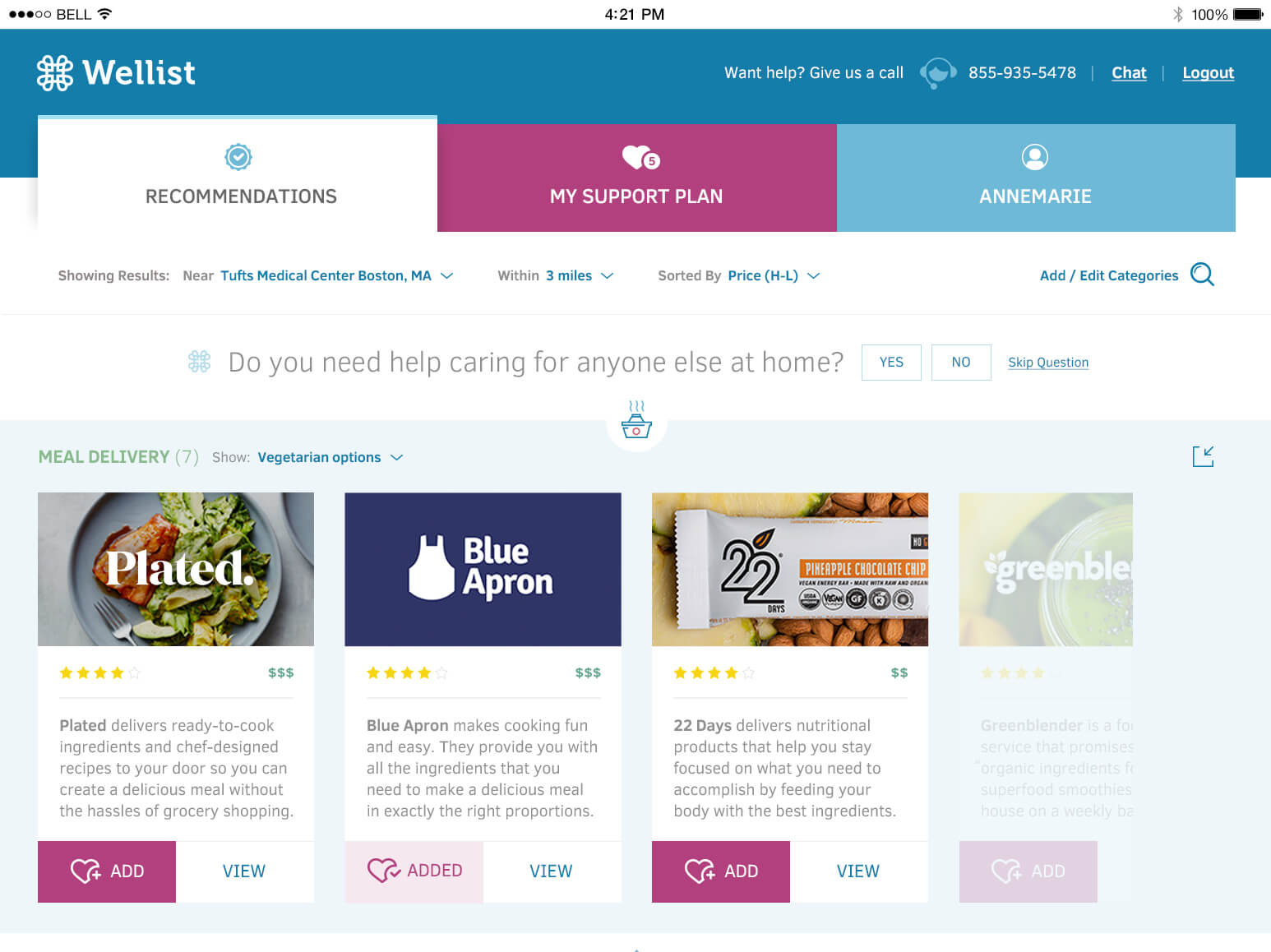

Learn from companies like Wellist, a virtual case manager that help people discover and use non-clinical services to improve their quality of life after a major diagnosis of life event like the birth of a child. Wellist engages users in a human, consultative discussion where every personal question asked informs recommendations to help people live their best life.

Never leave people asking “Why?”: Give consumers feedback and value for each personal disclosure. Any progressive profiling should feel like relationship-building, not data-mining. Interact with people as if they were people: A clinical voice can also be a human voice and as people disclose more to us, it’s our responsibility to respond with humanity.

Learn from companies like PillPack, who uses thoughtful design to demystify and organize people’s management of their medication, increasing adherence and avoiding negative interactions through pre-sorted medications packed by the dose.

Get to the point: Provide clear, straightforward information wherever and whenever possible. Design for everyone: Go beyond accessibility regulations and create content and design experiences that place a premium on patient understanding.

Learn from companies like Best Doctors, who helps people gain confidence in their healthcare by having the top physicians in the world review and their medical records and offer their expert perspective on diagnoses and treatment plans.

Use your expertise to inform patients: As patients share their information with you, return the favor with useful, expert information, and to the extent that it is appropriate, guidance to build their health aptitude. Know the limits of your role: Every interaction should have guardrails, with transparent, proactive notifications for when a patent interaction demands clinical intervention. To create experiences that people will embrace as we approach a time when companies can in theory know anything about the patients they might serve, respect of these people’s personal information, including the self-awareness and self-governance it will take to know when to say when enough is enough, will be a real differentiator.