Originally published on Koa Labs’ blog here.

Most of us in the world of marketing and product development are given one of two hats: strategy or creative. When talking with clients or peers, we might say “we’re on the strategy side of the business,” or that I’m “a creative.” Sometimes these separate roles manifest themselves in very physical realities, most agencies split their offices into departments: turn left for strategy, turn right for creative.

The brief was the thing that connected us – but conversely it also kept us apart. By providing clarity on the project objectives, target user behaviors and needs, as well as opportunities and constraints that would guide “the creative process”. The brief also represented in many ways, if not a culmination, at least a pause in the work of the strategy team who maybe, might later be called upon to answer questions, confirm that the creative is “on strategy,” or implement a measurement and analysis plan.

In our experience, the “hand-off” is both premature and self-defeating. The butterfly effect of whatever you create, should not be underestimated, for it has the potential to create a new reality with direct implications for strategy. The world isn’t static and your strategy shouldn’t be either.

That’s why we’ve increasingly shifted our understanding of the brief’s role in a project. It’s no longer the hand-off between strategy and creative, but instead it’s a tool used in the cross-disciplinary process of concepting and testing. Iterating on the solution requires iterating on the definition of the problem. From the whiteboard to the marketplace, there are countless opportunities to step back and build upon or even question the reality outlined in the brief, to advance the strategy in order to be relevant in the context of the new reality you are creating.

Concepting, in our experience is no longer the activity that happens as a result of strategy, instead it has become a critical part of the strategic process.

A few examples:

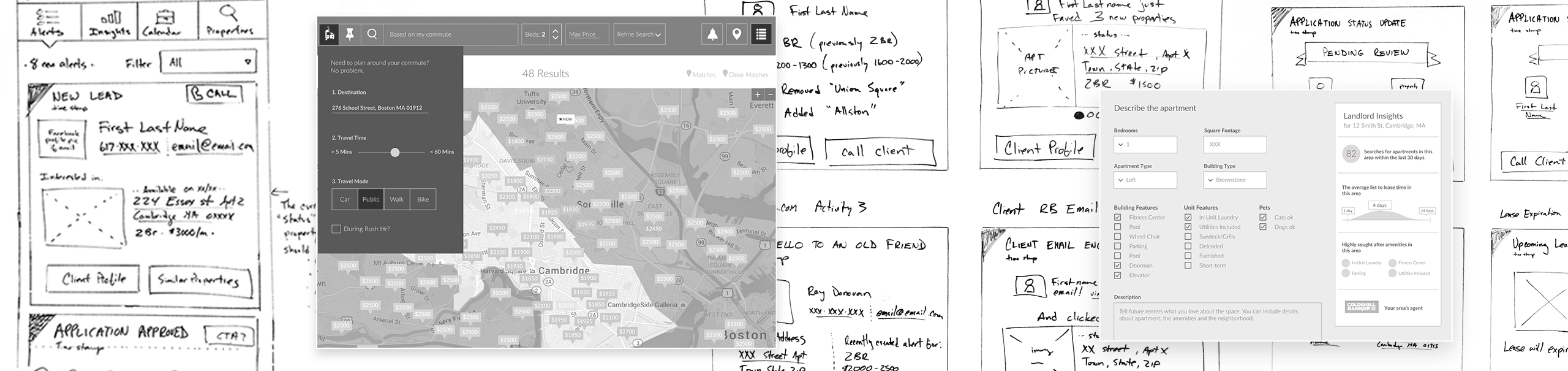

We recently completed work for a real estate firm whose core offering has been a lead-engine and CRM platform for brokers. They would acquire and serve leads using a proprietary database of residential rental listings and help brokers service those leads with a proprietary CRM platform to help them match properties against their clients needs and notify them when their clients would be back in the market.

As we started concepting the brokers’ CRM experience, we kept bumping up against the reality this tool was competing with an arsenal of other tools that brokers relied on to effectively do their jobs. In fact, the more we built out the CRM experience, the more it seemed to be in conflict with brokers’ other tools, effectively fragmenting their workflow and putting at risk the core benefits of our client’s offering. It was our client’s product. The tool we were to design couldn’t just be a lead-engine and CRM platform, but instead it had to be a hub for all of the brokers’ work-related activities: including tracking market trends, scheduling, coordinating visits with landlords, administration of lease documents, and inter- and intra-office team development and recognition. We realized that it wasn’t about using the market’s channels better, it needed to be about bring all those channels together into one clear, and more powerful tool, so that’s what we built.

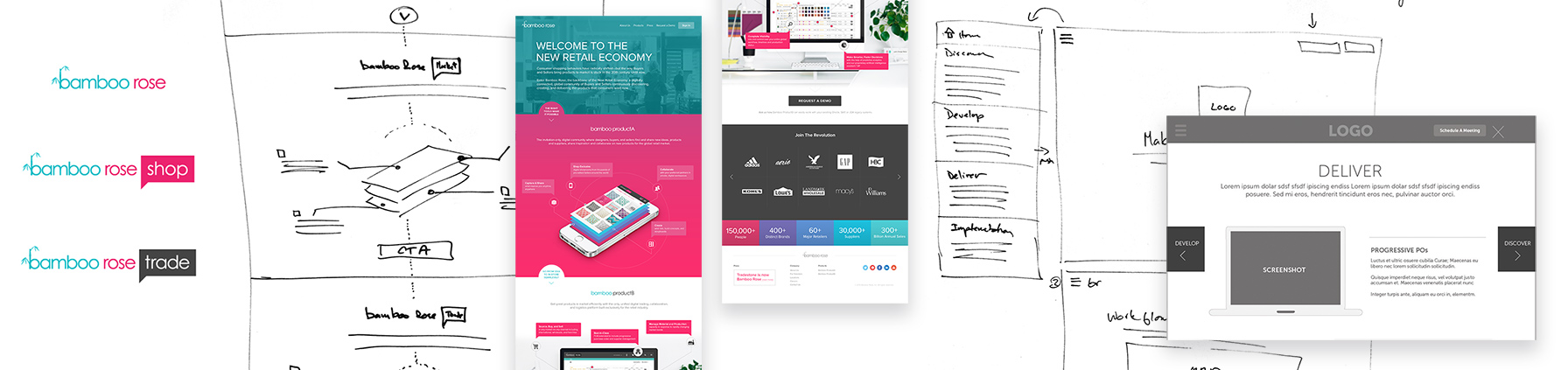

Too often testing is designed to answer simple questions like: “Do you like A or B?” or “Does this thing make sense to you? Why or why not?” But testing can be more than just the final gut check before investing in building and launching something, it can be integral in determining what that thing is. We were brought in to help a B2B technology firm craft a new go-to-market and branding strategy. They had multiple products, serving different users in a single important, though often overlooked industry – an industry that they were poised to revolutionize with a soon-to-be launched suite of products.

Through customer and expert interviews, we began to get speculative advice on the potential risks and opportunities the company might encounter by focusing its product strategy on a single offering instead of a suite of products and by changing its name. But almost all of the feedback boiled down to the fact that people would wait and see how things turned out, leaving the door open for a number of strategic directions.

To help advance the conversations and our strategic approach, we built concepts including product screens, marketing materials, and a website homepage to help customers see where this might go. This wasn’t a test of our recommendations; none of the concepts that we used at this stage ended up being a part of what we ultimately launched in market. Instead it was a test to inform our recommendation. Once people were able to see a few potential future realities they were better able to imagine how their relationship with the company might change if we pursued one, better able to advise on what we’d need to do in order to make each successful, what new risks might arise and what new opportunities might present themselves… it was this information, gathered entirely through concepting and testing that ultimately drove our in-market strategy.

Learning doesn’t stop at the usability lab. Often, targeted, in-market activations can provide the most reliable information to drive strategy. In working with a healthcare start-up to help them define their brand and launch a new marketing platform, we found ourselves in a number of long, spirited debates about what the future of healthcare meant to patients and what both excited and concerned them about it.

While everyone in the room for these debates was well-informed about the consumer healthcare market, we kept finding ourselves defending a point of view about this revolutionary new service by offering anecdotal evidence based on either competitors’ experiences or our own, budget-constrained research. The strategy at this point was grounded in projection and could easily be countered using the same, limited set of information.

In order to break the stalemate and (importantly for the start-up) start showing immediate results, we created a number of different marketing emails, each one representing a slightly different take on what the future of healthcare might mean, and the role our client could play in that future. Again, our initial concepts did not find their way into the marketing platform we finally launched, but the way in which people responded to the messages we tested directly informed everything that ultimately went to market.

If you or your clients are going to invest your time and money to create something new, a baseline expectation for that work should be that something will change as a result of it – your customers lives might get better, your business might grow, your community might improve. Too often though, strategy doesn’t reflect that change. It’s based on a retrospective view of the world before you did something. However, when you include concepting and testing in the strategic development process, you begin to account for that change and start building for the future as it will be thanks to you.

Don’t underestimate the change that is possible through your work, plan for it.